Disclaimer: I do not want this post to come across as whiny or pessimistic. I am highlighting an issue I see many of my peers also facing with the hopes that it will reach the relevant people who may be able to help us. Interpreting trainers or mentors- stick to the end, please!

The Financial Times has dubbed it the “Graduate Jobpocalypse”- We are living through (possibly) the worst graduate job market in history. Their recent video on the subject highlights AI and economic uncertainty as reasons why so many companies have been holding back on offering entry-level positions. Preferring to retain current staff over training up new graduates. After investigating the topic from several angles, and explaining that entry-level positions have dropped by a third this year alone, the FT conclude the video predicting a return to medieval-style work training, in which we will see a rise in companies charging for apprenticeships, or “indentured” labour, where, in return for training, graduates would be required to work for their company for 10 years or more. Whilst this information is delivered with the out-of-touch smile and fascination of somebody who will never have to experience the system she is theorising, the speaker’s words do raise some questions. I will touch on these later.

A glance at the comments on this video will show people’s outrage at this proposal, but even a quick dip into the job market will confirm that this is becoming a reality. Let’s dive into the graduate Jobpocalype: language industry edition.

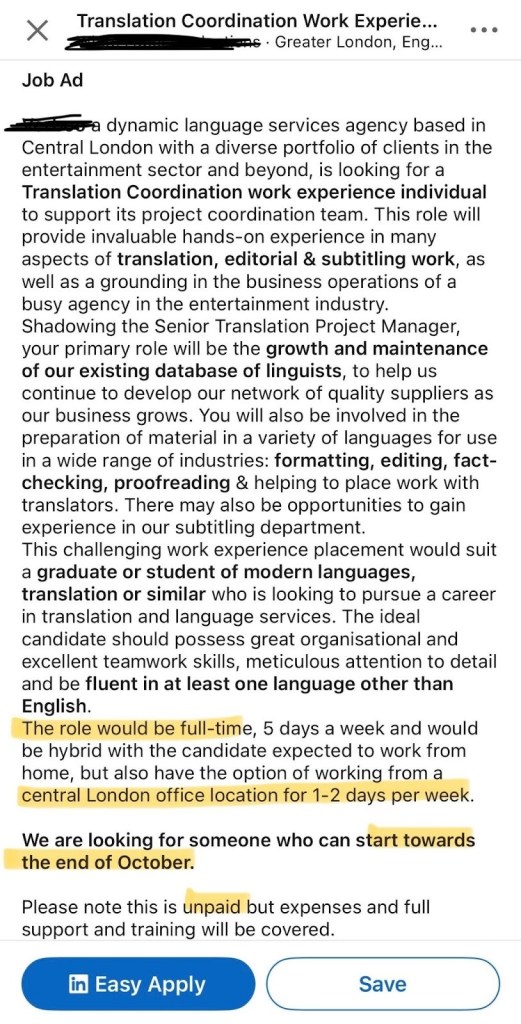

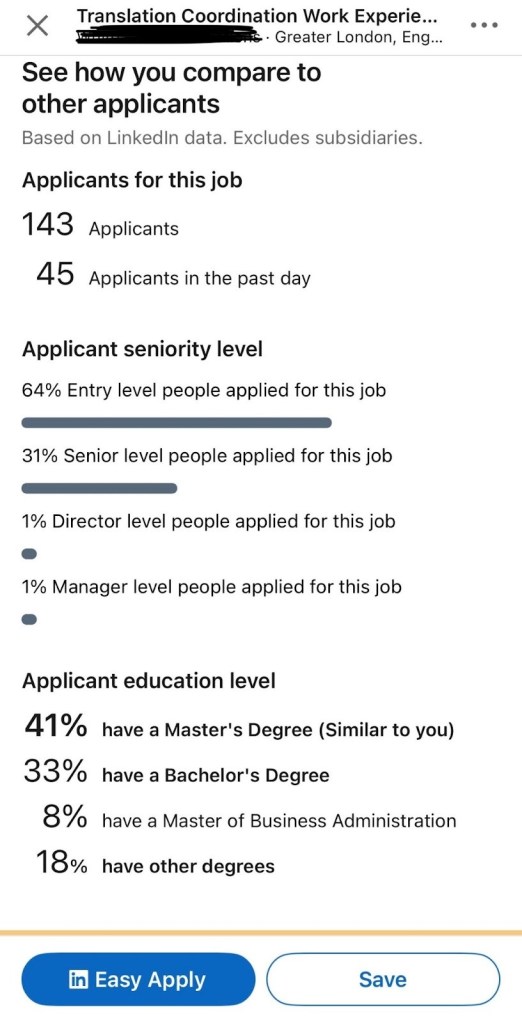

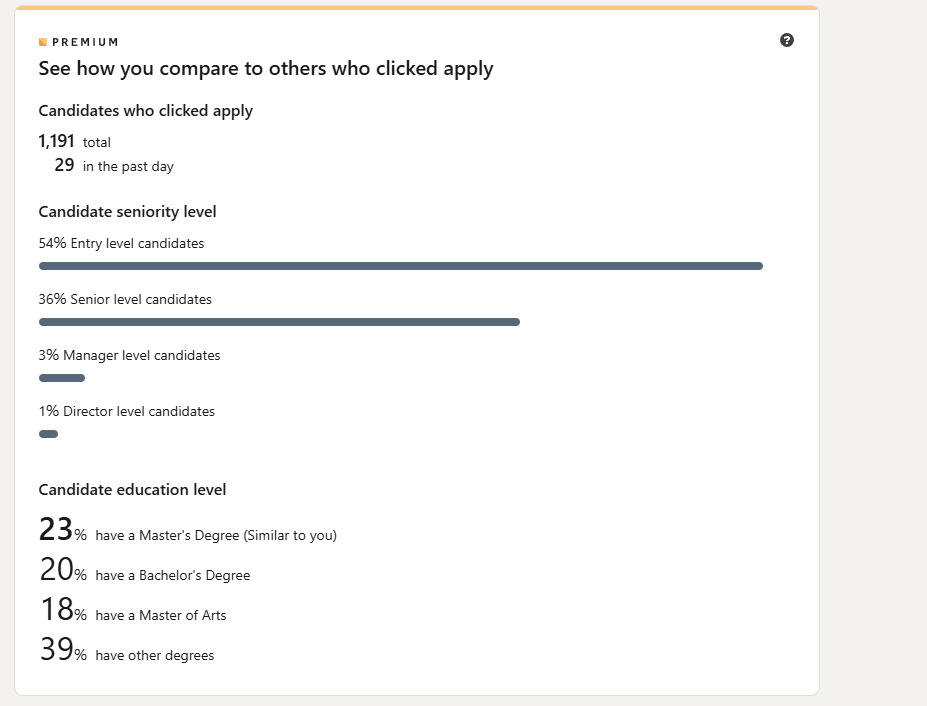

I have been seeing more and more unpaid Translation “Work Experience” offers in Central London pop up on my LinkedIn page, all with over a hundred applicants, like the one below. These offers include no mention of the length of the contract, no mention of any ascension in the company after a fixed period, nothing, not even the possibility of moving to a paid role. Yet, in just a few days, 143 people presented themself for the role below, of which almost half have a Master’s degree. So, after 80k+ debt in student loans, graduates are expected to work full-time for free in one of the world’s most expensive cities.

I would like to highlight here that this is not an internship. Many countries have established (but also arguably unfair) internship requirements in competitive fields, though this is less the case in the UK. The difference is that these are often agreements with universities to train a certain number of students alongside or after their studies in return for cheap or free labour. Crucially, these are fixed-term contracts offered to recent graduates, and there are many more positions offered than the odd one that gets posted to LinkedIn. This means that most graduates will undertake a, say, 6-month internship and use it as a stepping stone, often being taken on as a junior by the company afterwards. The “work experience” advertised here seems far more dubious. Like I said before, there is no mention in the advert of how long the unpaid contract would last, which I can only assume means it lasts indefinitely.

Let’s turn instead to the scary void of paid roles, where there really seems to be no point in applying to entry-level positions when they have over 1,000 applicants, many of whom, according to LinkedIn, are “senior level candidates”. If candidates with senior-level experience are willing to apply for entry-level jobs, why would the hiring team even consider taking someone on who would need training up? For reference, in the entry-level translation project manager job used below as an example, that’s over 400 candidates with senior experience.

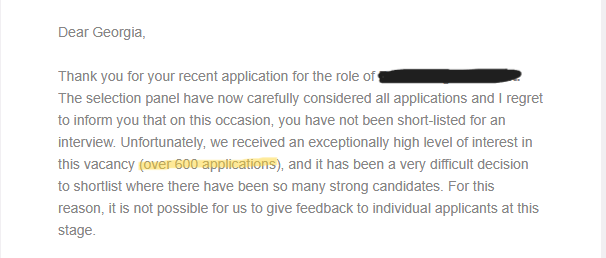

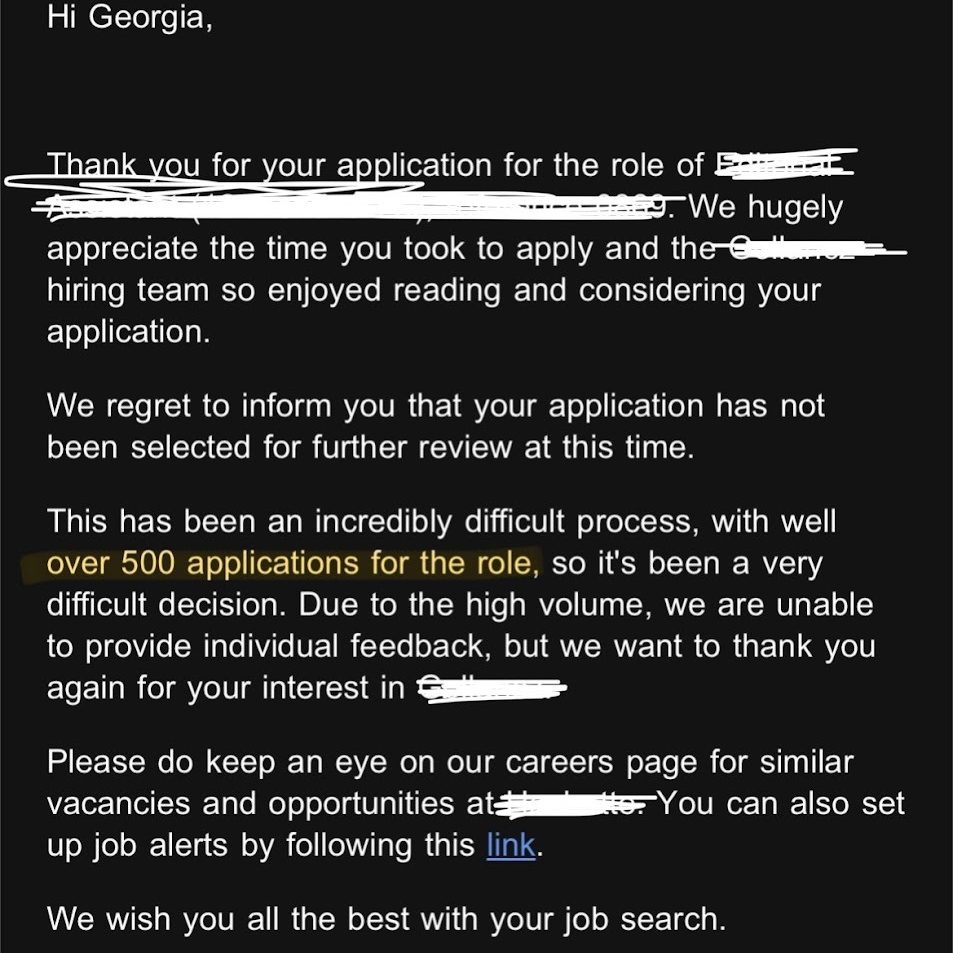

I used to see job rejection emails as a kind of personal failure, but now, when every single one mentions the sheer number of applications they received for one or two vacancies, it points to a flaw in the system. How can I really stand out in a crowd of even, say, 300 valid candidates?

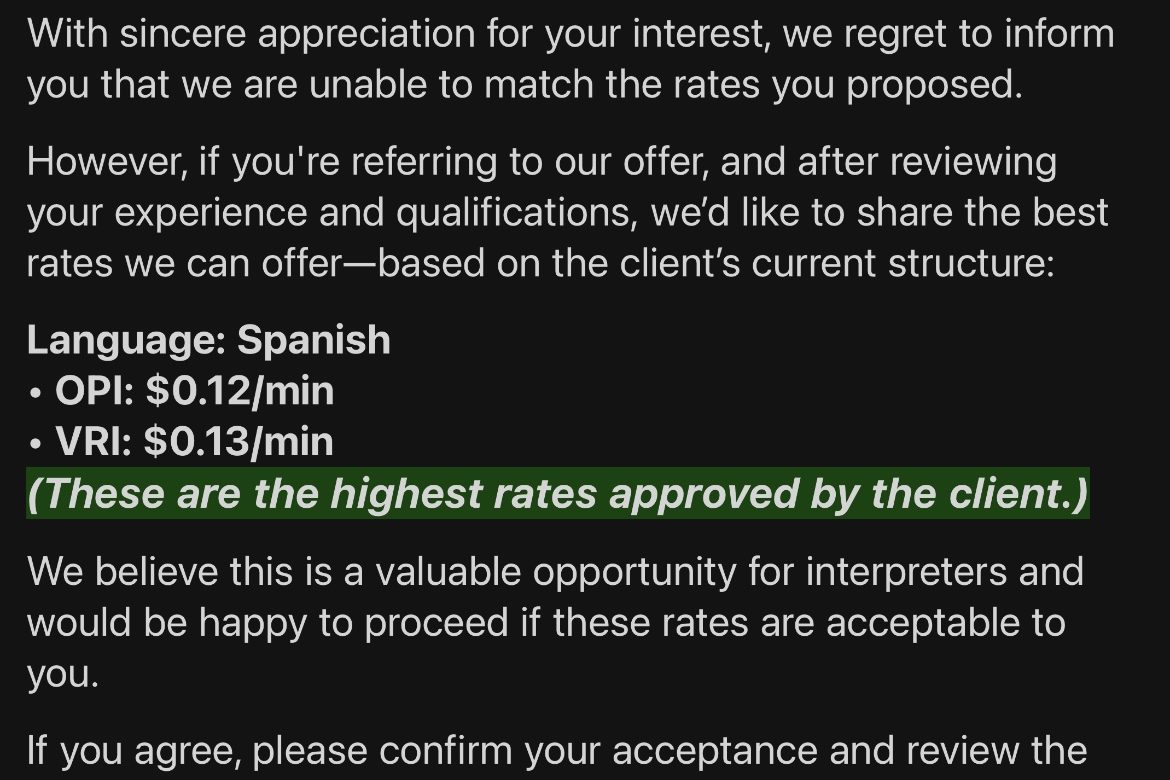

One of the reasons I have been interested in taking on a full-time position using my language skills has been my experience with freelancing. Whilst I absolutely adore my career (that’s why I studied it for 5 years at university), agencies offer new interpreters such insulting rates, like the whopping £5.40/h I was offered here for a “valuable opportunity” for an OPI agency (see below), that it makes you wonder how anyone can afford to gain experience as a linguist at all. I feel a moral obligation driven by many more senior interpreters’ complaints that accepting lower rates is impeding professionalisation and killing the industry to turn down agency offers that don’t cover travel expenses, or pay (below) minimum wage for jobs. However, new interpreters simply don’t have the experience to demand £0.1+/word for translation, or £40/h for interpreting. So, I atleast, find myself stuck between betraying my industry for experience, or working less (and earning less/gaining less experience), but upholding our values.

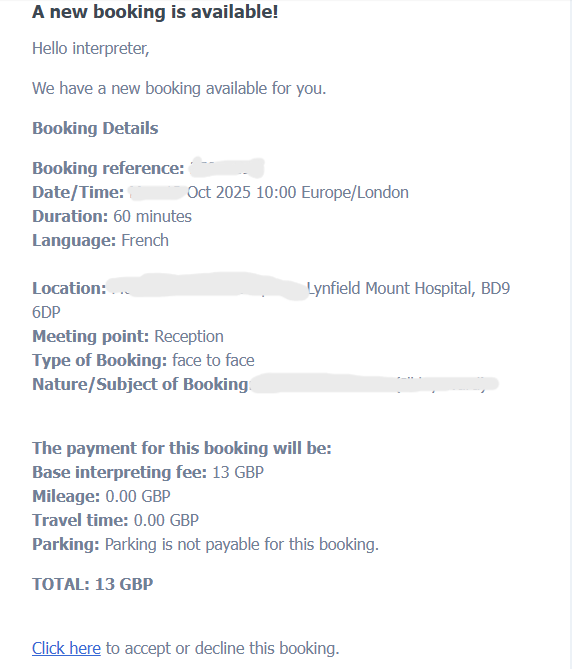

Obviously, I have turned down agencies offering rates such as those listed below. The hospital mentioned in the second image is a 9h round trip from my location, no travel expenses included, total pay: £13. (You’ve got to laugh at their “if you don’t ask you dont get” philosophy)

My ultimate goal is to be an interpreter forever. I want to work at international conferences, I want my voice to be a valuable tool for global diplomacy, and I want to help countries share, develop, and learn from one another. To get there in terms of experience, however, requires so much time earning the above rates that many simply cannot afford to dedicate the time to it. For example, to become a Chartered Linguist takes five years, or to become a member of the AIIC, you must demonstrate 150 days worked interpreting at conferences. These sorts of accreditations are sought after by the agencies that apparently pay decent rates to interpreters. This is a delicious spin-off of the old “needs experience to earn experience” vicious cycle, where you can earn experience only if you have the privilege of earning so little at first. Interpreters who do not have family they can live with after graduating, who aren’t able to have second and third jobs alongside their budding career, who have other time commitments (children, caring for family members, etc.) and cannot dedicate 15+ unpaid hours a week to CPD, are simply going to have to give up on their dreams. “Oh, but they can get another similar job using their language skills”. Can they? All of the example jobs in this post have been entry-level project managing, copywriting, and editing jobs that a translation/interpreting graduate could easily do. However, a specialised MA in translation and interpreting is not seen as so transferable as more general studies, say, journalism or communications degrees.

More experienced translators and interpreters who are going through “a drop in work” have the luxury of “diversifying”, “specialising”, or leaving the industry altogether and posting the benefits of these options on LinkedIn. I have been told so many times by senior interpreters to diversify my portfolio that the words are almost losing meaning. There is only so much CPD, volunteering, and extra degrees that the average person can afford. And, as we have seen, it is not as easy now to simply apply to a dubbing, subtitling, or copywriting assignment. I was once asked if I had ever considered moving to Brussels to seek work there. Beyond the whole Brexit factor, there are so many reasons why a 23-year-old recent graduate with limited professional experience wouldn’t be able to just up and move to another country in the hopes of finding freelance work. I have long had an issue with the out-of-touch, out-of-date, sometimes condescending, and most of all, incredibly vague nature of interpreting career tips from mentors and advisers.

My question is- is a successful career in translation/ interpreting truly a fantasy? A fluke? I see these incredible interpreters with over two decades in the field, EU and UN accreditations, memberships to every imaginable interpreting organisation, and their pages contain no mention of diversification at all. They appear to offer no editing, copywriting, dubbing, subtitling, or MTPE services of any kind; some don’t even mention translating. I have asked on many occasions how I can follow in the footsteps of those interpreters, but I have yet to receive a concrete or helpful answer, and I can only imagine hundreds of new interpreters are in a similar situation. Suggesting interpreters go into voice acting and dubbing seems like asking a news reporter to go into restaurant reviewing- yes they are similar and both involve writing, and the reporter might even enjoy dabbling in it, but once you turn away from reporting, you would lose your old writing style and total awareness of what is happening in the world, and struggle afterwards to re-enter the fold. Similarly, interpreting is such a niche, specialised skill that, if it is neglected early on in favour of anything else, it’s easy to lose.

Now, older folk I have discussed this with never fail to point out that it has always been hard to get a job, and that they too suffered similarly. So, if you are older and reading this with a wry smile, pondering the naivete and lack of perspective of the young, do not read this as a whiny, self-entitled moan about not being a world-renowned interpreter within a year of graduating, I invite you to instead view this post as more of an appeal to wisdom. The Financial Times called this “(possibly) the worst graduate job market in history”. Instead of thinking that young people aren’t willing to work hard or “pull themselves up by their bootstraps”, think of the struggles you had to build your career in times before AI and the internet, and consider the situation now. This is a genuine appeal to the elders of our community to reconsider their advice and think about how they can really help budding conference interpreters achieve their dreams.

I mean, “Become EU/UN-accredited” is not step one. There are hundreds of things that each accredited interpreter did before obtaining that status. I feel like there is a huge barrier between the hard-earned knowledge and experience of established interpreters and the unchanneled skills and ambition of newly-qualified interpreters. Is there a way we can work closer together? The Financial Times video highlighted the benefits of a “Master-Apprentice” training style, where young people accompany an expert in their job and learn from them by doing observing and participating until they are ready to take over from them once the master retires. Obviously, this is a tad exaggerated, but I would love to see less of an experience divide between career stages. I’m sure many young interpreters would leap at the opportunity to be taken under the wing of someone they can aspire to be, observe how they work, how they act and sell themselves, even if it were a on a completely voluntary basis.

I would genuinely love to talk more about this topic with an established conference interpreter, if any do read this and reflect. If not, insightful tips and advice are also welcome; I’m sure many across my network would benefit!

Leave a comment